Digitalisation of the Spanish agricultural sector

"The digital transformation in the agri-food sector is at a more advanced stage than initially thought". Plataforma Tierra analyses the results obtained by the Observatory of the Digitalisation of the Spanish Agri-Food Sector. It describes the degree of implementation of the new technologies available in the productive fabric of agriculture, livestock farming and the food industry, as well as the digital competence of its managers.

The Observatory of the Digitalisation of the Spanish Agri-Food Sector is an initiative of the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food coordinated by Cajamar. Its objective is to evaluate the degree of penetration and adoption of new technologies in the agri-food sector at both sub-sector and territorial level, along the entire value chain.

The study was carried out by means of a survey that involved the participation of 2,069 farmers, 666 livestock farmers and 890 food industry companies from all over Spain, during the months of July to November 2022.

Interconnectivity

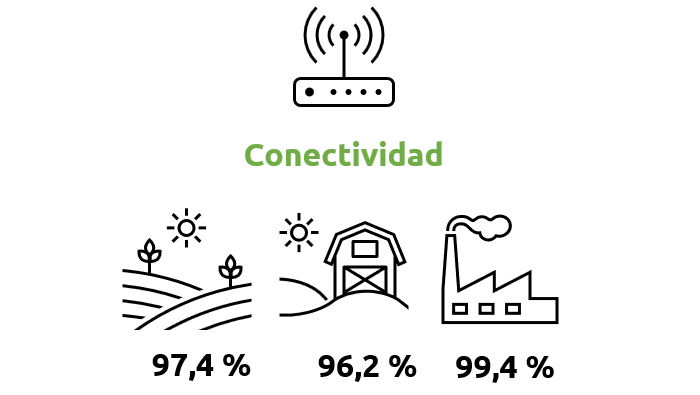

97.7% of agricultural, livestock and food industry players had some kind of internet connection, either fixed or mobile. But does this mean that the degree of connectivity of farms and food industries is adequate? The answer to this question depends. They reported an associated problem, which is the lack of a stable network over the entire surface area of their plots.

In short, high connectivity, but moderate network availability throughout the production site.

Digital capacity

Eight out of ten respondents had more than basic digital skills in software, information or problem solving. So much so that digital skills are higher than the average for the Spanish population.

Traditionally, there has been an disadvantaged view of the skills of primary producers, but as the results presented by the Observatory shows, this is not the case.

This does not mean that there is no need to improve the training of these people in various topics. They themselves request it, but in the same way as in other economic sectors. Practical training in the use of mass data analysis, artificial intelligence systems or other types of new digital technologies should be promoted.

But we must not lose focus either. The ageing of farmers is a fact, so they are going to have poorer digital skills and should be given all possible help to facilitate their adaptation to new technologies.

The most important data

One of the most important matters, according to Cajamar’s Plataforma Tierra, is the level of data collection in primary production. More than eight out of ten farmers collect data from their production units.

This figure drops to five out of ten in the food industry, although data from this sector should be treated with caution. They only refer to the type of sensors identified in the questionnaire, which is not the case for the primary production figure.

The large collection of data in the primary sector, provided it is shared appropriately, can catalyse the development of new decision-making systems based on artificial intelligence models.

However, this requires a platform that allows them to be made available in an anonymised form. Spain has a Data Office, but this involves the data collected by the production units to be transferred to this agency.

In short, It is necessary to create an appropriate national architecture for sharing agricultural data.

Automation

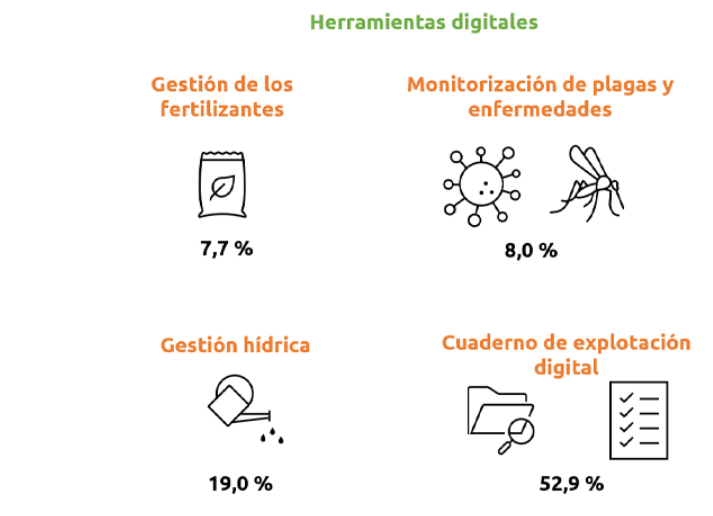

In terms of the use of digital tools in agriculture, the use of irrigation applications stood out. Two out of ten farmers used these tools.

Regarding the use of a digital field notebook, five out of ten farmers indicated that they used it. As this figure is possibly overestimated by the use of an Excel sheet as a field notebook, it is not representative.

As far as the use of automation is concerned, four out of ten farmers uses a tractor with digital assistance. And seven out of ten livestock farmers has some automated task. Here, feed distribution and environmental control within the farm facilities stood out.

Half of the farms and food industries used some kind of artificial intelligence system. However, there may have been confusion among respondents regarding the use of simple automation, which does not necessarily imply the use of an intelligent system.

In favour of digital transformation

Another interesting finding is that farmers and food companies are proactive in implementing new technologies. Almost seven out of ten primary producers were in favour of implementing new digital technologies and six out of ten food industries had developed or were developing a digitalisation strategy.

In other words, it can be seen that agri-food stakeholders are in favour of digitisation, whatever the internal motive that triggers this choice: improved environmental conditions, increased economic margins, etc.

However, some obstacles have to be overcome in order to do so. Among these, the following stand out:

- The high cost of new technologies, taking into account the possible high capital requirements of some of these new developments, the level of indebtedness of farmers themselves, which may hinder their willingness to implement new technologies, and, currently, the rise in interest rates.

- The scarcity of public funding, but at the same time an inadequate level of awareness of available support. For example, 50% of respondents were not aware of the Digital Kit. The Digital Kit Programme for the self-employed is a government initiative to promote the digitalisation of small businesses, micro-enterprises and professionals.

- The lack of training of agri-food sector stakeholders, referring to specific training in new technologies. For this purpose, they mostly request courses with a maximum duration of 15 hours in online format.

- Respondents doubt that the revenues triggered by digital innovations are adequate, although they recognise that they can increase productivity and lower costs.

Next steps

Plataforma Tierra ends this analysis as it began: "the agri-food sector, in terms of digitalisation, is not as bad as we thought at the beginning".

For this reason, we must improve the communication of the agri-food sector in order to transmit a real image of food production and processing. On the one hand, we have to offer an appropriate image to the consumer and, on the other hand, we have to retain and attract human capital and encourage the rejuvenation of players. As indicated by respondents, this can lead to increased productivity and lower production costs, which can translate into improved profit margins.

In addition, some digital disciplines such as robotisation can improve working conditions in the countryside, by assigning more labour-intensive tasks to other devices. Likewise, the use of digital tools in synergy with other technologies, such as the internet of things, the use of massive data analysis or artificial intelligence systems, will allow food production to be controlled in a delocalised manner.

Despite the “cutting-edge position” of the digitalisation of the Spanish agri-food system, we must not claim victory. In the coming years we will face a greater expansion of digital innovations in the countryside and, above all, of robotisation. To this end, we must carry out a greater exercise in communication and transfer, both of the innovations and of the availability of subsidies for their use.

At present, there is a low level of applications for subsidies for digitalisation, which is one of the obstacles to digital transformation, due to the high cost that some of the technologies can have.

See the full report in Spanish here: Observatorio de la Digitalización en el Sector Agroalimentario | Estudio 3 (plataformatierra.es)