The cycles to circularity: The path of Magdalena towards a more circular agriculture

According to the Dutch government’s vision, circular agriculture is the transition from a linear production system focused on continuously reducing cost prices while increasing production volumes and yields, towards a production system stressing the importance of putting as little pressure as possible on the environment, nature and climate. Not leaving aside profitability, circular agriculture aims at diminishing the use of raw materials and energy, improving soil, water and nature management, releasing as little waste and harmful emissions as possible, but also keeping residuals of agricultural biomass and food processing within the food system as renewable resources. Circular agriculture has to suit producers, consumers, nature and biodiversity, and their needs. Therefore, it poses common challenges that have to be solved collectively and beyond country boundaries. This article presents the activities related to circular agriculture supported by LAN Bogota in the Magdalena department in the north of Colombia.

Magdalena: between uniqueness and vulnerability

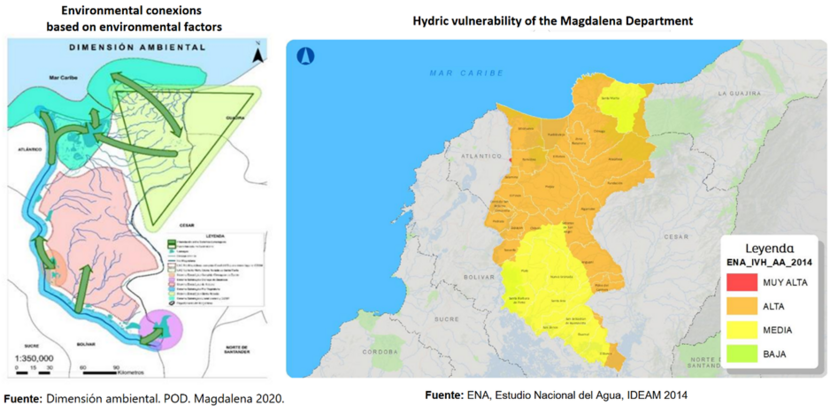

The Magdalena department stands amidst the Caribbean Sea, the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta (SNSM) and the Magdalena river. It has the largest surface of wetlands (humedales) and gathers all the climate zones and ecosystems available in Colombia. Now endangered by climate change, the Magdalena province has two unique landscapes. First, the Ciénaga Grande de Santa Marta (CGSM), the largest wetland and first site to be declared as a RAMSAR zone in the country. Second, a sacred territory for indigenous peoples, the SNSM is the highest mountainous complex (5,775 m.a.s.l.) in the world in proximity to the sea, declared by UNESCO as a Biosphere Reserve. The SNSM generates most of the (fresh) water available in the north of Colombia.

Both the SNSM and the CGSM have been highly affected by climate change and have been included in the listings of sites with the highest number of endangered species worldwide by the Alliance for Zero Extinction. The risks of natural disasters have been exacerbated by, among others, temperature increases, decreases in rainfalls, and prolonged periods of climatic phenomena (severe and long droughts during El Niño and floods during La Niña) caused by climate change. These negative impacts of climate change on the watersheds have been strengthened by human activities such as deforestation and illegal mining. Therefore, it is likely that the snow of the SNSM and the water reserves held at higher altitudes will be almost inexistent in the upcoming decade, worsening the prospects for the inhabitants on access to water for human consumption and agriculture.

The gates of agriculture

Agricultural products such as palm oil, bananas, coffee and avocados form an important part of the bilateral relationship between the Netherlands and Colombia. In fact, Colombia is the third largest coffee exporter worldwide, the third largest Hass avocado producer, and the fourth palm oil and banana supplier globally. The Netherlands (and the European Union) is one of the main destination markets for these and other Colombian agricultural products, where palm oil stands as the main agricultural export from Colombia to the Netherlands.

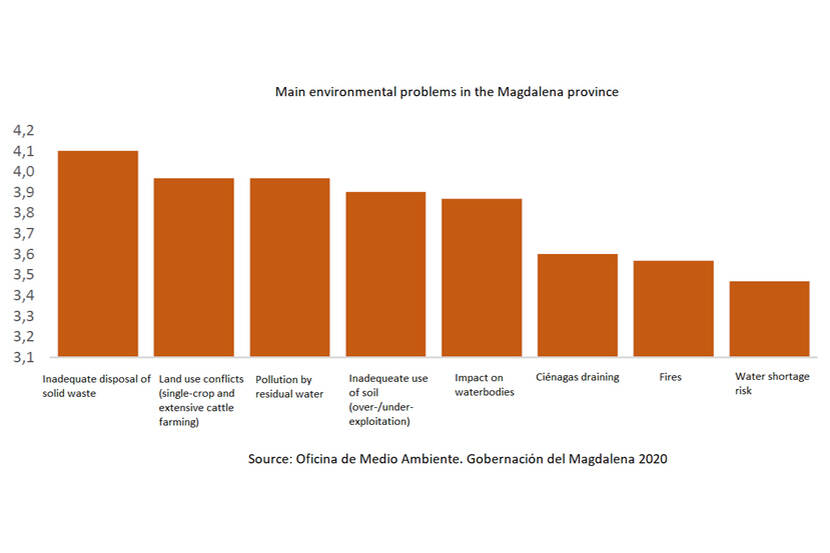

Many of these products that connect the Dutch (and European) market – via the ports of Rotterdam and Amsterdam – with Colombia are either grown in Magdalena or exported through the port of Santa Marta. As a matter of fact, primary agriculture is accountable for around 15% of Magdalena’s GDP, hence agriculture is one of its main economic activities. However, existing conflicts between land aptitude and land use are causing environmental problems in the region, which endanger water security as these conflicts entail deforestation, waterbodies desiccation, pesticides use and soil quality deterioration.

Circular agriculture: Putting policy into practice

In 2019 the Colombian government launched the National Strategy for Circular Economy, becoming a pioneer and the first country in Latin America to set the topic high in its political agenda. This policy aims at maximising the benefits of production and consumption systems in economic, environmental, and social terms, based on the circularity of flows of materials, energy and water. This policy emphasizes on six lines of action represented in six cycles: (i) Industrial materials and products; (ii) Packing and packaging materials; (iii) Biomass utilisation and optimisation; (iv) Water cycles; (v) Sources and use of energy; and, (vi) Management of urban material. Lines of action (ii), (iii) and (iv) are mostly linked to circular agriculture. Likewise, the Development Plan “Magdalena Renace” of the regional government sets sustainability as one of its strategic axes or “revolutions”, and circular economy – which makes special emphasis in agribusiness – is one of the lines of action or “mobilisations” to achieve this.

By reconciling the vision on circular agriculture of the Dutch Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality with the Colombian strategies on circular economy, Magdalena becomes a living lab wherein circular agriculture takes real steps towards concreteness. The following projects showcase how the Dutch- Colombian collaboration materialise those cycles that narrow circular economy into circular agriculture.

The water cycle: Putting the Netherlands’ renown to test

Due to increasing population and expanding agriculture, Magdalena is one of the regions with most critical water demand in Colombia. On the one hand, deforestation on higher altitudes in the SNSM, mainly associated to coca plants, coffee and cocoa cropping, has reduced upstream water retention and caused alarming levels of soil erosion, which ends up as sediments in the river basins born in the SNSM. This, along with water pollution caused by the postharvest process of coffee production, affects water quality for human and agricultural usage. On the other hand, in the downstream areas, water stress is evident from the large volumes of (surface and sometimes ground) water used inefficiently for crop irrigation due to poor know-how and technology at farm-level; while water scarcity causes productivity reductions for several crops. Hence, provoking a worrisome situation by the increased soil salinity in the CGSM and in the agricultural production areas.

Notwithstanding, agriculture, as the region’s main economic activity, is fundamental for food security as it plays a dual role of being a source of food as well as income (both from the sale of food products or employment generation). At the same time, agriculture being the main water user frames a different dimension/perspective of problems related to water. An individual analysis per crop helps better understanding these problems, while depicting the existing interrelations in a clearer way and proposing solutions:

- Palm oil and efficiency on water use: In the Northern region, around 750 palm oil producers are present who together cultivate a total of 130,000 ha. In the dry season palm oil producers use irrigation. Water is extracted from surface water, rivers, and in some cases groundwater is extracted via wells. Producers make use of surface irrigation, most of the time flood irrigation, an irrigation practice with little (or no) efficiency. Therefore, a Dutch-Colombian consortium led by Delphy in co-operation with Solidaridad Network, Future Water and Cenipalma (the Colombian research body of the palm oil industry) have been carrying out a cost-benefit analysis and feasibility study to investigate and address the limiting factors to adopt more efficient irrigation water techniques, like sprinkler or drip irrigation, which may offer a solution to reduce water stress. Read more: https://www.agroberichtenbuitenland.nl/landeninformatie/colombia/achtergrond/increased-water-efficiency-palm-oil---pvw

- Banana (and plantain) and water availability: This region faces a dry season of five to six months most often without any rains. During the dry season there is high water use in Magdalena, especially by banana and plantain, but also palm oil producers. This results in water scarcity and water stress which mainly affects the banana sector but other crops too. Climate predictions also show an increase in water scarcity in the near and far future, while water extractions are expected to grow. In accordance with this problem, the Dutch-Colombian consortium led by Deltares in collaboration with IHE Delft, Wageningen University and Research, Fundación Herencia Ambiental Caribe, ASBAMA, Tecbaco and Banasan, currently analyses the viability of introducing aquifers storage and recovery techniques in order to increase water availability for agricultural production.

- Coffee and water quality/pollution: The coffee sector is often blamed as one of the most water-polluting agricultural activities in Colombia, due to the effluents generated during the post-harvesting process. During this, the outer parts of the coffee cherry are removed from the endocarpal parchment by a physical and a fermentation process, resulting in two by-products: the pulp and a wastewater stream. Those products are characterised by a very high organic load, which usually is disposed into the water bodies, creating an important environmental impact, especially in areas with high concentration of coffee farms. The use of nature based solutions, such as vegetation filters (“filtros verdes”) or water-efficient coffee mills commonly referred to as an “eco-pulper” could be a suitable solution to reduce the pressure onto local water resources. But this transition can only take place when producers get paid a “true price” for their product. By paying a fairer price, supply chains are shortened, and consumers come closer to farmers, helping them moving away from non-sustainable production practices. Read more: https://www.agroberichtenbuitenland.nl/landeninformatie/colombia/achtergrond/tca-coffee

Threats to both water and food security configure the sense of urgency for a holistic watershed approach for an increased and improved water governance in the Magdalena department. Due to the abovementioned interrelations, information on water availability and usage, and on waste water impacts related to agricultural production needs to be collected and gathered in one multi-stakeholder platform. The information collected in the initiatives presented above, will serve as an indispensable input for decision making and finding solutions collectively to improve water governance. In consequence, the Dutch government supports the Water Stewardship Platform, a multi-stakeholder platform aimed at fostering dialogues and commitments between actors, chaired by WWF and Good Stuff International (GSI). Read more: http://plataformadecustodiadelagua.org/

From waste to energy: Biomass for biogas

Colombia is the leading producer and exporter of palm oil in Latin America, and a large supplier of this product for the Netherlands. The country allocates almost 500.000 hectares of its soil to oil palm cropping, which accounts for 7% of its agricultural GDP. Currently, the biomass resulting from palm oil production is burned for producing steam, but still the carbon footprint of this industry can be reduced while increasing the (economic) profits. Aiming at reducing the greenhouse gas emissions and operation costs of oil palm mills, a more circular set up for this industry is now being researched by Wageningen Food & Biobased Research (WFBR) in close collaboration with Cenipalma in order to make a more efficient use of this value chain’s resources.

Using biogas produced from Palm Oil Mill Effluents and from empty fruit bunches as the main power source for the mill offers a sustainable and profitable alternative to valorise oil palm biomass, which will, in turn, free-up the mesocarp fibre and shell. At the same time, the saved mesocarp fibre and palm shell can be sold for other uses such as energy production (saving coal) or material applications such as cellulose production and lignin (for asphalt production). Naturally, the biogas production process generates residues (known as digestate) and completely closing the cycle entails making use of these residues. Hence, the digestate can be returned to the field, thereby recycling the nutrients and recalcitrant biomass to the soil. As a result, this research proved that the production of biogas was sufficient to generate enough energy for running the mill.

Additionally, as a part of this collaboration WFBR applied the simulation model PALMSIM to assess potential and water limited yield of oil palm. After calibrating the model using local soil and yield data from different oil palm companies, water limited potential yields were simulated based on soil and plantation weather data. Therefore, by increasing yields per hectare bringing them closer to their potential levels, greenhouse gas emissions are reduced, and both soil and biodiversity – central elements in circular agriculture – are preserved.

Biomass and plastics: The virtuous cycle

In Colombia, banana growing is often accompanied by plantain cropping. In combination, these two crops account for almost 50% of the permanent crops in Magdalena. High quality standards of international markets forced the Colombian banana and plantain agribusiness to include plastic in the production process back in the seventies. Products such as high and low density polyethylene packaging bags, “field bags” to protect fruit bunches, plastic tapes to identify the age of the fruit and polypropylene rope to avoid trees’ breaking due to fruit bunches’ weight or wind currents, apparently became inseparable from banana and plantain production in Colombia. In consequence, each year the production of banana and plantain entails large amounts of post-industrial plastic waste. This plastic, especially fabricated for this industry, presents certain difficulty when being recycled because, during the 13 weeks of the production cycle, both the field bag and the mooring rope are in the open air and at the time of harvesting it may contain high amounts of moisture, soil and latex from the plant.

Therefore, the introduction of bio-based and/or biodegradable plastics to replace fossil plastics while making better use of biomass offers a feasible alternative to reduce plastic waste and greenhouse gas emissions from the Colombian banana and plantain sector. Besides, these bio-based plastics find additional market potential in Colombia due to the significant sizes of the fruit, vegetable and flower industries that traditionally have used transparent fossil plastic packaging materials to deliver end products to consumers. In that sense, there is a growing demand for a more sustainable alternative, economically and technically competitive. A Dutch company together with WFBR has developed technology to produce bioplastics from starch containing agri-residues, together with other bio-based ingredients and has marketed several starch based plastics over the past 20 years. Recently, a consortium composed by WFBR and various Colombian partners (Cenipalma, Cenibanano, Augura and Daabon) have expressed their interest to examine the viability of producing local “starch plastics” from agricultural residues – including banana and oil palm residues – and the potential markets for starch plastics in Colombia, like bags to cover banana and plantain bunches or food packaging.

Author: Andrés Santana Bonilla